Feminist and Anti-Racist Philosophies of Science [6-weeks, $250 Suggested]

Instructor: Andrews | Wednesdays 7:00-9:00 PM | September 14-October 19

[**Note date change: originally slated to begin September 7]

In the wake of climate change and a global pandemic, the refrain “believe science” has become a progressive dictum and moral charge. But what does that mean exactly? What is “science,” and what do we mean by ideas often associated with it such as “objectivity” and “method”? For almost as long as most contemporary scientific disciplines have existed, scientists and others have been asking these questions, and those attuned to feminist and anti-racist thought have quickly come to realize that the practices and interpretations of science are not value-neutral knowledge. Many of us are aware that, for example, scientific medical research has engaged in unethical experiments on people of color; in the past biology was used to prove the “fact” of binary sex and the “inferiority” of women; or that scientific “advancement” has been used to justify technologies that expedite environmental degradation that disproportionately affects minority communities. So we will ask: How have race and gender shaped our understandings of ourselves and our world? How has that knowledge been applied in ways that often disadvantage or exploit raced and gendered groups? And how have researchers and activists been fighting against the sometimes pernicious use of science and reimagining the very idea of “knowledge”? The aim of this course will be to dismantle a totalizing conception of science (as “good” or “bad”) and instead to understand how scientific knowledge and practices are (re)produced in and through culture. Over the course of four weeks, we’ll learn about feminist concepts such as “strong objectivity” (Harding) and anti-racist theories of “fugitive science” (Rusert). We’ll consider the ways that non-white, women, and gender non-conforming people have contributed to scientific knowledge, and we’ll ask what truly anti-racist and feminist sciences might look like. Authors may include: Katherine McKittrick, Sandra Harding, Britt Rusert, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Harriet Washington, Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, Alondra Nelson, and Ruha Benjamin, among others.

—

For each class, four (4) full tuition scholarships and five (5) 80% tuition scholarships are available. Due to limited scholarship funds, we are currently only able to offer one class per term at the full scholarship level to any individual student—if you need a full scholarship, please sign up for the class you most want to take and email us to waitlist for any additional classes. We will add you when funds become available. Direct student donations are a crucial aspect of our funding model, and without them, we are not able to pay instructors a living wage. We encourage you to pick the payment tier that corresponds with your needs, but ask that you please consider our commitment to fair labor practices when doing so. If the scholarship tier you need is sold out or you would like to pay tuition on an installment basis, please email us directly, and we will work with you.

If at any point up to 48 hours before your first class session you realize you will be unable to take the class, please email us and we will reallocate your funds to a future class, to another student’s scholarship, or refund it. After classes begin, we are only able to make partial refunds and adjustments.

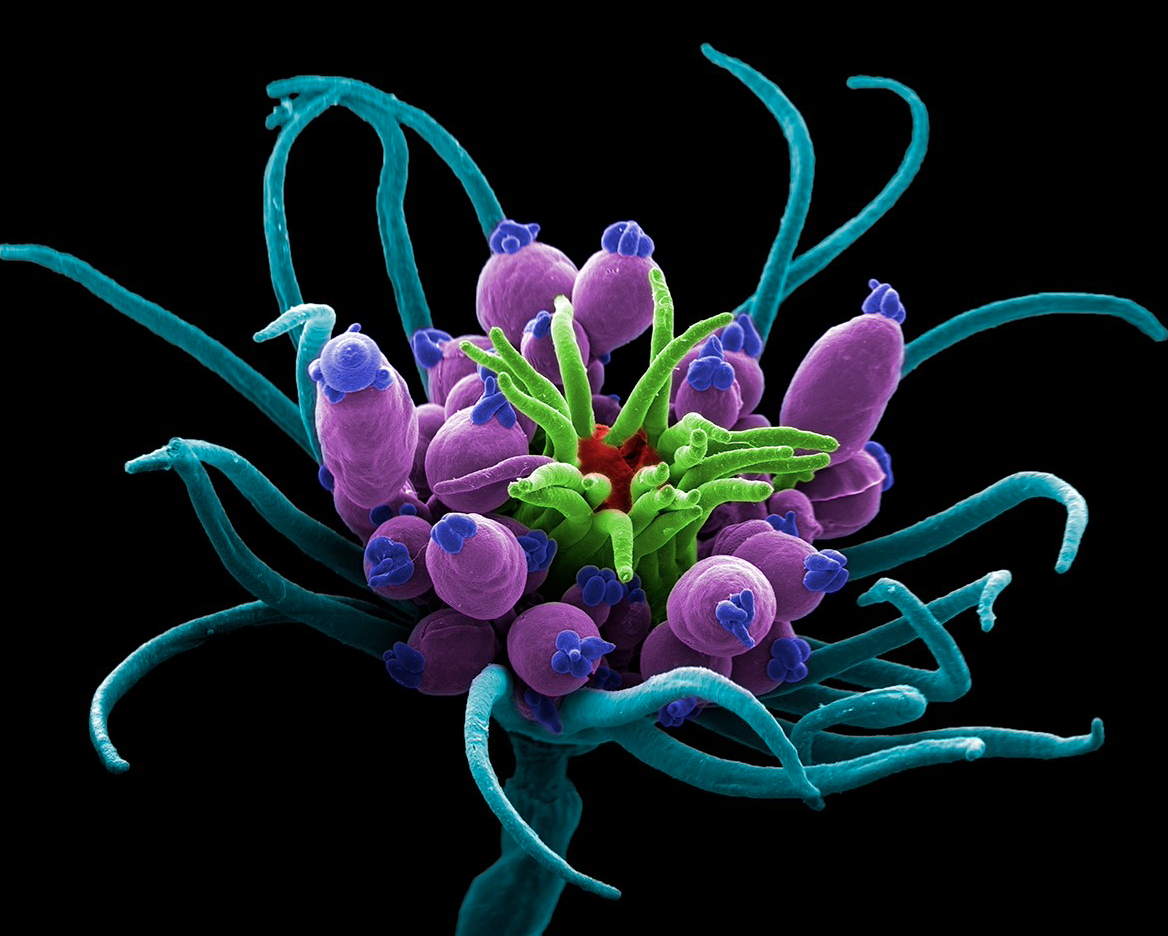

Photo credit: Jannicke Wiik-Nielsen/Science Photo Library

Instructor: Andrews | Wednesdays 7:00-9:00 PM | September 14-October 19

[**Note date change: originally slated to begin September 7]

In the wake of climate change and a global pandemic, the refrain “believe science” has become a progressive dictum and moral charge. But what does that mean exactly? What is “science,” and what do we mean by ideas often associated with it such as “objectivity” and “method”? For almost as long as most contemporary scientific disciplines have existed, scientists and others have been asking these questions, and those attuned to feminist and anti-racist thought have quickly come to realize that the practices and interpretations of science are not value-neutral knowledge. Many of us are aware that, for example, scientific medical research has engaged in unethical experiments on people of color; in the past biology was used to prove the “fact” of binary sex and the “inferiority” of women; or that scientific “advancement” has been used to justify technologies that expedite environmental degradation that disproportionately affects minority communities. So we will ask: How have race and gender shaped our understandings of ourselves and our world? How has that knowledge been applied in ways that often disadvantage or exploit raced and gendered groups? And how have researchers and activists been fighting against the sometimes pernicious use of science and reimagining the very idea of “knowledge”? The aim of this course will be to dismantle a totalizing conception of science (as “good” or “bad”) and instead to understand how scientific knowledge and practices are (re)produced in and through culture. Over the course of four weeks, we’ll learn about feminist concepts such as “strong objectivity” (Harding) and anti-racist theories of “fugitive science” (Rusert). We’ll consider the ways that non-white, women, and gender non-conforming people have contributed to scientific knowledge, and we’ll ask what truly anti-racist and feminist sciences might look like. Authors may include: Katherine McKittrick, Sandra Harding, Britt Rusert, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Harriet Washington, Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, Alondra Nelson, and Ruha Benjamin, among others.

—

For each class, four (4) full tuition scholarships and five (5) 80% tuition scholarships are available. Due to limited scholarship funds, we are currently only able to offer one class per term at the full scholarship level to any individual student—if you need a full scholarship, please sign up for the class you most want to take and email us to waitlist for any additional classes. We will add you when funds become available. Direct student donations are a crucial aspect of our funding model, and without them, we are not able to pay instructors a living wage. We encourage you to pick the payment tier that corresponds with your needs, but ask that you please consider our commitment to fair labor practices when doing so. If the scholarship tier you need is sold out or you would like to pay tuition on an installment basis, please email us directly, and we will work with you.

If at any point up to 48 hours before your first class session you realize you will be unable to take the class, please email us and we will reallocate your funds to a future class, to another student’s scholarship, or refund it. After classes begin, we are only able to make partial refunds and adjustments.

Photo credit: Jannicke Wiik-Nielsen/Science Photo Library

Instructor: Andrews | Wednesdays 7:00-9:00 PM | September 14-October 19

[**Note date change: originally slated to begin September 7]

In the wake of climate change and a global pandemic, the refrain “believe science” has become a progressive dictum and moral charge. But what does that mean exactly? What is “science,” and what do we mean by ideas often associated with it such as “objectivity” and “method”? For almost as long as most contemporary scientific disciplines have existed, scientists and others have been asking these questions, and those attuned to feminist and anti-racist thought have quickly come to realize that the practices and interpretations of science are not value-neutral knowledge. Many of us are aware that, for example, scientific medical research has engaged in unethical experiments on people of color; in the past biology was used to prove the “fact” of binary sex and the “inferiority” of women; or that scientific “advancement” has been used to justify technologies that expedite environmental degradation that disproportionately affects minority communities. So we will ask: How have race and gender shaped our understandings of ourselves and our world? How has that knowledge been applied in ways that often disadvantage or exploit raced and gendered groups? And how have researchers and activists been fighting against the sometimes pernicious use of science and reimagining the very idea of “knowledge”? The aim of this course will be to dismantle a totalizing conception of science (as “good” or “bad”) and instead to understand how scientific knowledge and practices are (re)produced in and through culture. Over the course of four weeks, we’ll learn about feminist concepts such as “strong objectivity” (Harding) and anti-racist theories of “fugitive science” (Rusert). We’ll consider the ways that non-white, women, and gender non-conforming people have contributed to scientific knowledge, and we’ll ask what truly anti-racist and feminist sciences might look like. Authors may include: Katherine McKittrick, Sandra Harding, Britt Rusert, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Harriet Washington, Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, Alondra Nelson, and Ruha Benjamin, among others.

—

For each class, four (4) full tuition scholarships and five (5) 80% tuition scholarships are available. Due to limited scholarship funds, we are currently only able to offer one class per term at the full scholarship level to any individual student—if you need a full scholarship, please sign up for the class you most want to take and email us to waitlist for any additional classes. We will add you when funds become available. Direct student donations are a crucial aspect of our funding model, and without them, we are not able to pay instructors a living wage. We encourage you to pick the payment tier that corresponds with your needs, but ask that you please consider our commitment to fair labor practices when doing so. If the scholarship tier you need is sold out or you would like to pay tuition on an installment basis, please email us directly, and we will work with you.

If at any point up to 48 hours before your first class session you realize you will be unable to take the class, please email us and we will reallocate your funds to a future class, to another student’s scholarship, or refund it. After classes begin, we are only able to make partial refunds and adjustments.

Photo credit: Jannicke Wiik-Nielsen/Science Photo Library